AGAFIA LYKOVA WAS BORN WHILE HER FAMILY WAS LIVING ALONE IN THE WILDERNESS. SHE IS THE ONLY SURVIVING MEMBER OF THE FAMILY. SPUTNIK VIA AP

THIS RUSSIAN FAMILY LIVED ALONE IN THE SIBERIAN WILDERNESS FOR 40 YEARS, UNAWARE OF WORLD WAR II OR THE MOON LANDING

BY: MIKE DASH; UPDATED BY ELLEN WEXLERORIGINAL SITE: SMITHSONIAN MAGAZINE

In 1978, Soviet geologists stumbled upon a family of five in the taiga. They had been cut off from almost all human contact since fleeing religious persecution in 1936.

Siberian summers do not last long. The snows linger into May, and the cold weather returns again during September, freezing the taiga into a still life awesome in its desolation: endless miles of straggly pine and birch forests scattered with sleeping bears and hungry wolves; steep-sided mountains; white-water rivers that pour in torrents through the valleys; thousands of miles of icy bogs. This forest is one of the last and greatest of Earth’s wildernesses. It stretches from Russia’s Arctic regions to as far south as Mongolia, and east from the Urals to the Pacific: millions of square miles of sparsely populated nothingness.

When the warm days do arrive, though, the taiga blooms, and for a few short months it can seem almost welcoming. It is then that man can see most clearly into this hidden world—not on land, for the taiga can swallow whole armies of explorers, but from the air. Siberia is the source of most of Russia’s oil and mineral resources, and, over the years, even its most distant parts have been overflown by oil prospectors and surveyors on their way to backwoods camps where the work of extracting wealth is carried on.

Thus it was in the remote south of the forest in the summer of 1978. A helicopter sent to find a safe spot to land a party of geologists was skimming the tree line 100 or so miles from the Mongolian border when it dropped into the thickly wooded valley of an unnamed tributary of the Abakan River , a seething ribbon of water rushing through dangerous terrain. The valley walls were narrow, with sides that were close to vertical in places, and the skinny pine and birch trees swaying in the rotors’ downdraft were so thickly clustered that there was little chance of finding a spot to set the aircraft down.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/33/f0/33f09488-fa83-493b-9398-d3473a8bb56e/gettyimages-1154193170.jpg)

The Lykov family lived in remote regions of the Siberian taiga for more than 40 years—utterly isolated and more than 150 miles from the nearest human settlement - Amzanyta via Getty Images

However, peering intently through his windscreen in search of a landing place, the pilot saw something that should not have been there. It was a clearing on a mountainside, wedged between the pine and larch and scored with what looked like long, dark furrows. The baffled helicopter crew made several passes before reluctantly concluding that this was evidence of human habitation—a garden that, from the size and shape of the clearing, must have been there for a long time.

It was an astounding discovery. The mountain was more than 150 miles from the nearest settlement in an area that had never been explored. The Soviet authorities had no records of anyone living in the district.

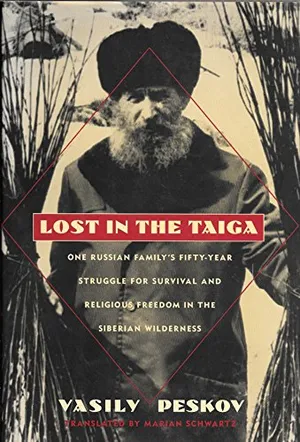

The four scientists sent into the district to prospect for iron ore were told about the pilots’ sighting, and it perplexed and worried them. “In the taiga, it’s less dangerous to run across a wild animal than a stranger,” as Russian journalist Vasily Peskov wrote in Lost in the Taiga: One Russian Family’s 50-Year Struggle for Survival and Religious Freedom in the Siberian Wilderness . Rather than wait at their own temporary base, ten miles away, the scientists decided to investigate. The group’s leader, a geologist named Galina Pismenskaya, said they “chose a fine day and put gifts in our packs for our potential friends”—though, just to be sure, she recalled, “I did check the pistol that hung at my side.”

Lost in the Taiga

A Russian journalist provides a haunting account of the Lykovs, a family of Old Believers, or members of a fundamentalist sect, who in 1932 went to live in the depths of the Siberian Taiga and survived for more than fifty years apart from the modern world.

As the intruders scrambled up the mountain, heading for the spot pinpointed by their pilots, they began to come across signs of human activity: a rough path, a staff, a log laid across a stream and finally a small shed filled with birch-bark containers of cut-up dried potatoes. Pismenskaya told Peskov:

Beside a stream there was a dwelling. Blackened by time and rain, the hut was piled up on all sides with taiga rubbish—bark, poles, planks. If it hadn’t been for a window the size of my backpack pocket, it would have been hard to believe that people lived there. But they did, no doubt about it. … Our arrival had been noticed, as we could see.

The low door creaked, and the figure of a very old man emerged into the light of day, straight out of a fairy tale. Barefoot. Wearing a patched and repatched shirt made of sacking. He wore trousers of the same material, also in patches, and had an uncombed beard. His hair was disheveled. He looked frightened and was very attentive. … We had to say something, so I began: “Greetings, grandfather! We’ve come to visit.”

The old man did not reply immediately. … Finally, we heard a soft, uncertain voice: “Well, since you have traveled this far, you might as well come in.”

The sight that greeted the geologists as they entered the cabin was like something from the Middle Ages. Jerry-built from whatever materials came to hand, the dwelling was not much more than a burrow—“a low, soot-blackened log kennel that was as cold as a cellar,” with a floor consisting of potato peel and pine-nut shells, wrote Peskov. Looking around in the dim light, the visitors saw that it consisted of a single room. It was cramped, musty and indescribably filthy, propped up by sagging joists—and, astonishingly, home to a family of five. As Pismenskaya told the author:

[The] silence was suddenly broken by sobs and lamentations. Only then did we see the silhouettes of two women. One was in hysterics, praying: “This is for our sins, our sins.” The other, keeping behind a post … sank slowly to the floor. The light from the little window fell on her wide, terrified eyes, and we realized we had to get out of there as quickly as possible.

Led by Pismenskaya, the scientists backed hurriedly out of the hut and retreated to a spot a few yards away, where they took out some provisions and began to eat. After about half an hour, the door of the cabin creaked open, and the old man and his two daughters emerged—no longer panicked and, though still obviously frightened, “frankly curious.” Warily, the three strange figures approached and sat down with their visitors, rejecting everything that they were offered—jam, tea, bread—with a muttered, “We are not allowed that!” When Pismenskaya asked, “Have you ever eaten bread?” the old man answered: “I have. But they have not. They have never seen it.” At least he was intelligible. The daughters spoke a language distorted by a lifetime of isolation. “When the sisters talked to each other, it sounded like a slow, blurred cooing.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ee/54/ee545ea4-588d-4734-b3d6-6759c334c839/gettyimages-113635573.jpg)

Peter the Great’s attempts to modernize the Russia of the early 18th century found a focal point in a campaign to end the wearing of beards—which was anathema to Karp Lykov and the Old Believers - Universal History Archive / Getty Images

Slowly, over several visits, the full story of the family emerged. The old man’s name was Karp Osipovich Lykov, and he was an Old Believer —a member of a fundamentalist Russian Orthodox sect, worshiping in a style unchanged since the 17th century. Old Believers had been persecuted since the days of Peter the Great, and Lykov talked about it as though it had happened only yesterday. For him, Peter was a personal enemy and “the Antichrist in human form”—a point he insisted had been amply proved by the czar’s campaign to modernize Russia by forcibly “[chopping] off the beards of Christians.” These centuries-old hatreds were conflated with more recent grievances; Karp was prone to complain in the same breath about a merchant who had refused to make a gift of 26 poods of salt to the Old Believers sometime around 1900. As the geologists filled him in on what he’d missed, he used a similar lens to form opinions about current events:

The events that had excited the world were unknown here. The Lykovs did not know any famous names and had heard only vaguely about the past war. When in recalling the “first world war” with Karp Osipovich the geologists engaged him in conversation about the last one, he shook his head: “What is this, a second time, and always the Germans. A curse on Peter. He flirted with them. That is so.”

Things had only gotten worse for the Lykov family when the atheist Bolsheviks took power. Under the Soviets, isolated Old Believer communities that had fled to Siberia to escape persecution began to retreat ever further from civilization. During the purges of the 1930s, with Christianity itself under assault, a Communist patrol had shot Lykov’s brother on the outskirts of their village while Lykov knelt working beside him. He had responded by scooping up his family and bolting into the forest .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a4/3a/a43a6200-1298-4d0e-8db2-c0753d6e22e7/russian_family_8.jpg)

The Lykovs' homestead seen from a Soviet reconnaissance plane, 1980

That was in 1936, and there were only four Lykovs then—Karp; his wife, Akulina; a son named Savin, who was around 9 years old; and Natalia, a daughter who was only 2. Taking their possessions and some seeds, they had retreated ever deeper into the taiga, building themselves a succession of crude dwelling places, until at last they had fetched up in this desolate spot. Two more children had been born in the wild—Dmitry in 1940 and Agafia in 1944—and their knowledge of the outside world came entirely from their parents’ stories. The family’s principal entertainment, Peskov noted, “was for everyone to recount their dreams.”

The Lykov children knew there were places called cities where humans lived crammed together in tall buildings. They had heard there were countries other than Russia. But such concepts were no more than abstractions to them. Their only reading matter was prayer books and an ancient family Bible. Akulina had taught her children to read and write using sharpened birch sticks dipped into honeysuckle juice as pen and ink. When Agafia was later shown a video of a horse on the geologists’ television set, she recognized it from her mother’s stories. “A steed!” she exclaimed. “Papa, a steed!”

But if the family’s isolation was hard to grasp, the unmitigated harshness of their lives was not. Traveling to the Lykov homestead on foot was astonishingly arduous, as Peskov would later learn firsthand. On his first visit to the Lykovs in the 1980s, the writer—who would appoint himself the family’s chief chronicler—noted that “we traversed 250 kilometers [155 miles] without seeing a single human dwelling!”

Isolation made survival in the wilderness close to impossible. Dependent solely on their own resources, the Lykovs struggled to replace the few things they had brought into the taiga with them. They fashioned birch-bark galoshes in place of shoes. Clothes were patched and repatched until they fell apart, then replaced with hemp cloth grown from seed.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c7/86/c7861f2d-f328-463b-ac87-c7d39b7eeff5/russian_family_2.jpg)

The Lykovs lived in this hand-built log cabin, lit by a single window and warmed by a smoky wood-fired stove.

The Lykovs had carried a crude spinning wheel and, incredibly, the components of a loom into the taiga with them. A couple of kettles served them well for many years, but when rust finally overcame them, the only replacements they could fashion came from birch bark. Since these could not be placed in a fire, it became far harder to cook. By the time the Lykovs were discovered, their staple diet was potato patties mixed with ground rye and hemp seeds.

In some respects, Peskov wrote, the taiga did offer abundance: “Beside the dwelling ran a cold, clear stream. Stands of larch, spruce, pine and birch yielded all that anyone could take. … Bilberries and raspberries were close to hand, firewood as well, and pine nuts fell right on the roof.”

Yet the Lykovs lived permanently on the edge of famine. It was not until the late 1950s, when Dmitry reached manhood, that they first trapped animals for their meat and skins. Lacking guns or even bows, they could hunt only by digging traps or pursuing prey across the mountains until the animals collapsed from exhaustion. Dmitry built up “astonishing endurance” and could hunt barefoot in winter, sometimes returning to the hut after several days with a young elk across his shoulders. More often than not, though, there was no meat, and their diet gradually became more monotonous. Wild animals destroyed their crop of carrots, and Agafia recalled the late 1950s as “the hungry years”:

We ate the rowanberry leaf, roots, grass, mushrooms, potato tops and bark. We were hungry all the time. Every year we held a council to decide whether to eat everything up or leave some for seed.

Famine was an ever-present danger in these circumstances, and in 1960 it snowed in June. The hard frost killed everything growing in their garden, and by spring the family had been reduced to eating leather shoes, bark and straw. Akulina chose to see her children fed, and in February 1961 she died of starvation.

The rest of the family were saved by what they regarded as a miracle: a single grain of rye sprouted in their pea patch. The Lykovs put up a fence around the shoot and guarded it zealously night and day to keep off mice and squirrels. At harvest time, the solitary spike yielded 18 grains, and from this they painstakingly rebuilt their rye crop.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6f/d6/6fd6e023-a7a8-4e70-b57c-ed9c6d8dad2c/russian_family_7.jpg)

A Russian press photo of Karp Lykov (second left) with Dmitry and Agafia, accompanied by a Soviet geologist

As the Soviet geologists got to know the Lykov family, they realized that they had underestimated their abilities and intelligence. Old Karp was usually delighted by the latest innovations that the scientists brought up from their camp, and though he steadfastly refused to believe that man had set foot on the moon, he adapted swiftly to the idea of satellites. The Lykovs had noticed them as early as the 1950s, when “the stars began to go quickly across the sky,” and Karp himself conceived a theory to explain this: “People have thought up something and are sending out fires that are very like stars.”

“What amazed him most of all,” Peskov recorded, “was a transparent cellophane package. ‘Lord, what have they thought up—it is glass, but it crumples!’” Even at the end of his life, when he was in his 80s, Karp held grimly to his status as head of the family. His eldest child, Savin, dealt with this by casting himself as the family’s unbending arbiter in matters of religion. “Savin was strong in his faith, but he was a harsh man,” his own father said of him, and Karp seems to have worried about what would happen to his family after he died if Savin took control. Certainly the eldest son would have encountered little resistance from Natalia, who always struggled to replace her mother as cook, seamstress and nurse.

The two younger children, on the other hand, were more open to change and innovation. “Fanaticism was not terribly marked in Agafia,” Peskov wrote, and in time he came to realize that the youngest of the Lykovs “had a sense of humor and irony and knew how to poke fun at herself.” Agafia’s unusual speech—she had a singsong voice and stretched simple words into polysyllables—convinced some of her visitors she was slow-witted. On the contrary, she was markedly intelligent, helping Savin with the difficult task, in a family that possessed no calendars, of keeping track of time. She thought nothing of hard work, either, excavating a new cellar by hand late in the fall and working on by moonlight when the sun had set. Asked by an astonished Peskov whether she was not frightened to be out alone in the wilderness after dark, she replied: “What is there to be afraid of?”

Of all the Lykovs, though, the geologists’ favorite was Dmitry, a consummate outdoorsman who knew all of the taiga’s moods. He was the most curious and perhaps the most forward-looking member of the family. It was he who had built the family stove, and all the birch-bark buckets that they used to store food. Perhaps it was no surprise that he was also the most enraptured by the scientists’ technology. Once relations had improved to the point that the Lykovs could be persuaded to visit the Soviets’ camp, downstream, he spent many happy hours in its little sawmill, marveling at how easily a circular saw and lathes could finish wood. “It’s not hard to figure,” Peskov wrote. “The log that took Dmitry a day or two to plane was transformed into handsome, even boards before his very eyes. Dmitry felt the boards with his palm and said: ‘Fine!’”

Karp Lykov fought a long and losing battle with himself to keep all this modernity at bay. When they first got to know the geologists, the family would accept only a single gift—salt. (Living without it for four decades, Karp said, had been “true torture.”) Over time, however, they began to take more. They welcomed the assistance of their special friend among the geologists—a driller named Yerofei Sedov, who spent much of his spare time helping them to plant and harvest crops. They eventually accepted blankets, wool socks, grain and even a flashlight. Once, when Agafia was asked why she would use a battery-powered flashlight when she wouldn’t accept matches, she “didn’t know how to respond,” wrote Peskov. “She only confirmed that matches were indeed a sinful thing.” Meanwhile, the sin of television, which the family encountered at the geologists’ camp, “proved irresistible for them”:

On their rare appearances in camp, they would invariably sit down and watch. Karp Osipovich sat directly in front of the screen. Agafia watched, poking her head out from behind a door. She tried to pray away her transgression immediately—whispering, crossing herself—and once again stuck her head out. The old man prayed afterward, diligently and in one fell swoop.

Perhaps the saddest aspect of the Lykovs’ strange story is the rapidity with which the family went into decline after they re-established contact with the outside world. In the fall of 1981, three of the four children followed their mother to the grave. According to Peskov, their deaths were not, as some have speculated , the result of exposure to diseases to which they had no immunity. Both Savin and Natalia suffered from kidney failure, most likely a result of their harsh diet. But Dmitry died of pneumonia, which might have begun as an infection he acquired from his new friends.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2b/c4/2bc48668-d13a-40b0-b577-a4bf2200ad5b/russian_family_9.jpg)

The Lykovs' graves. Today, Agafia is the only surviving member of the family of six.

His death shook the geologists, who tried desperately to save him. They offered to call in a helicopter and have him evacuated to a hospital. But Dmitry, in extremis, would abandon neither his family nor the religion he had practiced all his life. “We are not allowed that,” he whispered just before he died. “A man lives for howsoever long God grants.”

When all three Lykovs had been buried, the geologists attempted to talk Karp and Agafia into leaving the forest and returning to be with relatives who had survived the persecutions of the purge years, and who still lived on in the same old villages. But neither of the survivors would hear of it.

Agafia did accept one invitation around this time. The Soviet government offered to take her on tour across the country, and she agreed to go. Her father stayed behind, but she spent a month on the road, soaking up everything she had missed. When the trip ended, she returned to her old life. “It’s scary out there,” Agafia told Vice in 2013. “You can’t breathe. There are cars everywhere. There is no clean air. Each car that passes by leaves so many toxins in the air. You have no other option but to stay at home.”

Soon after Agafia’s sojourn, Karp Lykov died in his sleep on February 16, 1988, 27 years to the day after his wife, Akulina. Agafia buried him on the mountain slopes with the help of the geologists, then turned and headed back to her home. The Lord would provide, and she would stay , she said—as indeed she did. “The taiga reclaimed her,” author Isabel Colegate wrote in A Pelican in the Wilderness: Hermits, Solitaries and Recluses . “She felt it was her home.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/05/78/057865c3-53b1-48bf-adc4-49450e717869/ap792731058301.jpg)

Agafia Lykova receiving medical care in 2016. She continued to live in remote locations after her father’s death, though she has traveled on rare occasions - Yekaterina Romanova / Komsomolskaya Pravda via AP

More than 30 years later, this child of the taiga lives on in the wilderness. However, as her health has declined—she turned 80 earlier this year—she has started accepting more help . Lately, much of that help comes from the Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska , who paid for a new wooden cottage to be built for her several years ago. She also acquired a satellite telephone, which she uses daily, and volunteers frequently travel to her isolated home to deliver supplies and help her manage daily affairs, particularly during the cold winters.

Agafia will not leave. But we must leave her, seen through the eyes of Sedov on the day of her father’s funeral:

I looked back to wave to Agafia. She was standing by the river break like a statue. She wasn’t crying. She nodded: “Go on, go on.” We went another kilometer and I looked back. She was still standing there.

Mike Dash is a contributing writer in history for Smithsonian.com. Before Smithsonian.com, Dash authored the award-winning blog A Blast From the Past.

AWFSM CATEGORIES

Activism | AI | Belief | Big Pharma | Conspiracy | Cult | Culture | Deep State | Economy | Education | Entertainment | Environment | Faith | Global | Government | Health | Hi Tech | Leadership | Politics | Prophecy | Science | Security | Social Climate | Universe | War