Ethnic Profiling of Tigrayans Heightens Tensions in Ethiopia

EMMANUEL FREUDENTHAL

‘There was some pressure from my neighbours, my friends, everywhere.’

This story was co-reported by a journalist in Addis Ababa whose name is being withheld for security reasons.

The fighting between Ethiopia’s federal government and the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) wasn’t a surprise to Tigrayans living in Addis Ababa: They had seen it coming for years. What they didn’t expect was to be living in fear so far away from the front lines.

Speaking with The New Humanitarian in a series of interviews over the past month, half a dozen Tigrayans living in the country’s capital described ethnic profiling and growing harassment. Such abuse and discrimination by neigbours, strangers, and government officials could, analysts and others warn, widen the rift among Ethiopia's increasingly polarised ethnic groups, leading to renewed conflict.

“The war drums have been sounding for years,” said Million Gebremedhin, a Tigrayan restaurant owner who has lived in Addis Ababa since 2014. “The war is not a surprise. But what came after the war, the way [Abiy] is doing it, is a surprise.”

A month of clashes between government forces and fighters loyal to the ruling party in the Tigray region has displaced an estimated one million people, according to the UN, and killed thousands.

Phone and internet connections were partially restored in Tigray on 14 December, and the first international humanitarian convoy – seven trucks carrying medicine and supplies from the International Committee of the Red Cross – made its way into Mekelle, the region’s capital, on 12 December.

The country’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, has insisted the military efforts are a “law enforcement operation” targeting leaders of the TPLF – which he refers to as a “criminal clique” – and not the wider Tigrayan community.

But Tigrayan refugees who have fled to neighbouring Sudan have accused the Ethiopian army and allied militias of attacking civilians.

Read more → Tigray refugees recount the horrors of Ethiopia's new conflict

The Ethiopian Human Rights Commission, which is appointed by the state, said it was “gravely concerned” at reports of ethnic profiling of Tigrayans, “most notably manifested in forced leave from work and in stopping people from travelling overseas including on work missions, for medical treatment or studies”.

Some of the Tigrayans who spoke to TNH said the abuse began before the recent conflict. Most said they had stayed home over the past month out of fear they might be arrested and accused of supporting the TPLF. One has now left Ethiopia completely. All were worried about the safety of their relatives in Tigray, which lies hundreds of kilometres north of the capital.

“The war is not a surprise. But what came after the war, the way [Abiy] is doing it, is a surprise.”

A man in his mid-thirties said he was having coffee in Addis Ababa with a group of friends – some speaking Tigrinya, the language spoken in Tigray – when a neighbour he had known for two years passed by and shouted: “Tigrayan troublemakers, why are you congregating?”

“I couldn’t believe she had said that to us,” the man, who asked for his name to be withheld because of fear of reprisals, told TNH.

Analysts say anti-Tigrayan discrimination could unify the community – which does not uniformly support the TPLF – against the central government. It could also widen tensions between communities in Ethiopia, some of which are pushing for greater power and autonomy. The TPLF and allied militias have been accused of attacks on ethnic Amhara during the recent fighting too.

“The ethnic profiling demonstrates that despite the government’s stated intention to target only the TPLF leadership, this conflict is also having a much broader negative impact on Tigrayans outside of Tigray,” said William Davison, an analyst at the International Crisis Group.

In an email interview with TNH, Laetitia Bader, the Horn of Africa director at Human Rights Watch, said her organisation has received reports of Tigrayans outside of the northern region being harassed on the street, profiled at airports and cafes, and having their homes arbitrarily searched by Ethiopian security forces.

“The discrimination by state agents could fuel further discrimination or harm,” Bader said. “The government should immediately investigate these incidents, hold those responsible to account, and make clear that any violence, discrimination, or hostility against Tigrayans or any other group will not be tolerated.”

Media reports claim that Tigrayan soldiers serving on an African Union peacekeeping mission fighting Islamist insurgents in Somalia have had their weapons removed . And Tigrayan employees at Ethiopian Airlines – pilots, caterers, technicians, and security guards among them – have reportedly been instructed by their superiors to stay at home until further notice.

High-profile Tigrayans have also been accused by the government of supporting the TPLF. In November, Ethiopia’s army chief said – without providing evidence – that the head of the World Health Organization, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, was trying to procure weapons and secure diplomatic support for the Tigrayan party. Tedros denied the allegations .

Bank accounts frozen, homes searched

Only six percent of Ethiopia's more than 100 million population live in Tigray, but officials from the region have dominated the country politically since the TPLF led a guerrilla struggle that defeated the country’s Marxist regime in 1991.

The party was at the centre of a political coalition called the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), which governed the country with an authoritarian apparatus for almost 30 years.

Abiy came to power in 2018 on the back of mass anti-government protests that channelled popular discontent with the EPRDF’s authoritarian rule, and the power wielded by the TPLF, which had a disproportionate influence in civilian and security structures and in key business sectors.

Officials from the TPLF have since been arrested on corruption charges and removed from federal positions and state institutions, fuelling a sense of discrimination among party members.

"To capture the top criminals in the TPLF, the government breaks the hopes, lives, and dreams of so many."

Tigrayans, who said they had no connections to the TPLF, told TNH they have felt targeted too. Some said they have found it harder to get jobs in recent years because of their ethnicity; others said they have fallen out with their neighbours and friends.

The situation has worsened over the past month. Several of the Tigrayans said police officers have harassed them on the streets of Addis Ababa after checking their identity cards, which indicate their region of birth.

Alleging looting and corruption, the National Bank of Ethiopia ordered the suspension of bank accounts opened in Tigray, from mid-November to 3 December , according to reports in local media. It also ordered bank branches to close in the region.

The freeze affected three of the six Tigrayans in Addis Ababa. One provided a photograph of their bank teller’s computer screen, which confirmed the account was not working.

Fearing arrest or physical assault if they leave their houses, some of the Tigrayans told TNH they haven’t worked for weeks and fear their savings will run out.

One woman, originally from Tigray, said members of her family who work for the government had their homes searched by armed men who took an inventory of their valuable household items – including their fridge, sofa and jewellery – shortly after the conflict broke out.

The woman, who asked to remain anonymous, said her Tigrayan-sounding surname now “terrifies” her. She worries her family will be asked to leave the house they live in, which is provided for by the government.

"To capture the top criminals in the TPLF, the government breaks the hopes, lives, and dreams of so many", she said.

Gebremedhin – who left Mekelle six years ago to set up his business in Addis Ababa – said his life has become more difficult since Abiy took charge.

The restaurant owner, who is in his thirties, recalled an incident in 2018 when Abiy labelled opponents of his reform agenda “ daytime hyenas ” – a phrase Gebremedhin and many others argue has been used to vilify Tigrayans, whether Abiy meant it to or not.

Gebremedhin said his friends began to distance themselves from him after that point, and loyal customers started boycotting his restaurant, which is located in Addis Ababa’s Haya Hulet neighbourhood, where many eateries are owned by Tigrayans.

"I was doing good, but… after Abiy has come to power, there was some pressure from my neighbours, my friends, everywhere,” Gebremedhin said. “They [asked], 'are you with the government?'"

Despite explaining he was a businessman – not a politician – Gebremedhin said his friends accused him of supporting the old regime. “You don't [seem] to support this government... you guys, we don't trust,” Gebremedhin recalled his friends saying. “You [are] always with the old system, with the TPLF."

The restaurant owner said events took a turn for the worse after the murder in June of Hachalu Hundessa – a popular Oromo singer and activist – sparked violent protests in Oromia region that cost more than 200 lives.

The government accused the TPLF and Oromo nationalists of fomenting the protests. Soon after, Gebremedhin said young men who came to drink in his restaurant started smashing bottles and refusing to pay, forcing the establishment to close.

"Security-wise I could not continue to work," Gebremedhin said.

Trapped relatives

While worrying about their lives in Addis Ababa, the Tigrayans who spoke to TNH have also been concerned for the welfare of their relatives and friends stuck in Tigray.

The government claimed victory after capturing Mekelle late last month, but the TPLF has said its forces are continuing to fight, and the UN says clashes persist on multiple fronts.

In its latest humanitarian update , the UN’s emergency aid coordination agency, OCHA, describes shortages of food, water, fuel, and cash, and a lack of medical supplies that is disrupting critical health services.

Gebremedhin, the restaurant owner – who sobbed when asked about his relatives in Mekelle – said the war could push Tigrayans in the north to want to secede from Ethiopia – a constitutional right afforded to each of the country’s 10 ethnically based regions.

He said it used to be the case that 10 to 20 percent of Tigrayans would think like that, while more like 80 percent regarded themselves as Ethiopian. “But now, after the war… I’m sure if I say I’m Ethiopian to my people there, they will hate me.”

Addressing the alleged discrimination she has suffered, the woman whose home was searched said: “Either [the government] are doing it without knowing the consequences, or they’re really out to get Tigrayans all over the country and create a new enemy.”

Ethnic Violence in Tigray has Echoes of Ethiopia’s Tragic Past

LAURA HAMMOND

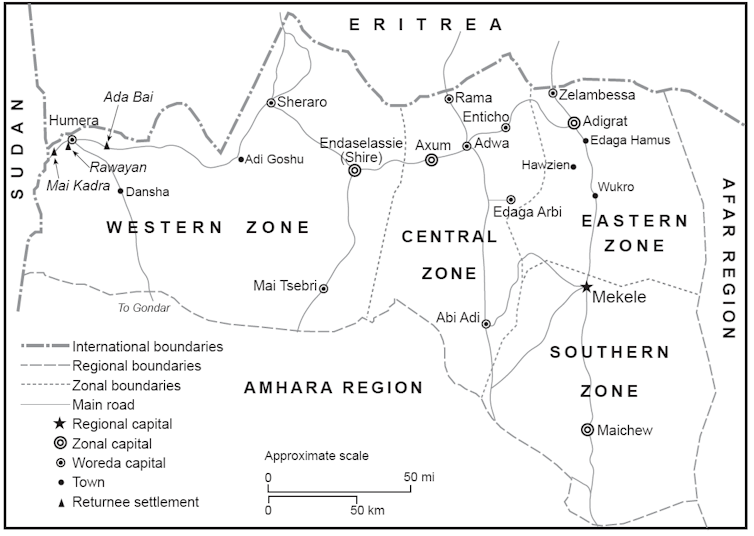

Violence has engulfed northern Ethiopia and, as usual, it is the civilians caught in the middle of this bitter ethnic conflict who are paying the highest price. Amnesty International reported on November 12 that a brutal massacre had taken place in the town of Mai Kadra in the northwestern province of Tigray. Scores – maybe hundreds – of people, described by Amnesty as seasonal labourers, were killed with knives and machetes.

Fighting has also been reported near the border town of Humera where the Ethiopian army is understood to have wrested control of the airport from the Tigray People’s Liberation Army (TPLF). So far an estimated 25,000 people have fled to Sudan, including from the Humera area , an area that can be seen as a microcosm of the tensions that are pulling at the complex ethnic fabric across Ethiopia.

Ethiopia’s ‘Casablanca’

Back in 1993, while I was casting around looking for potential PhD research sites, a friend and colleague recommended I go to Humera, a town in the far northwest corner of Ethiopia. “It’s like an Ethiopian Casablanca,” he told me. I duly went to check it out. What I found held not so much the mystique of an old Islamic city but a bustling community of Tigrayan former refugees who had recently been repatriated after a decade in camps in eastern Sudan where they had sought refuge during the civil war that raged in Ethiopia from 1974 to 1991.

Originally highlanders, they were resettled into the fertile lowlands around Humera with the expectation that they would become smallholder farmers, supplementing their incomes working on the commercial sesame and sorghum farms in the area. Humera itself was a war-ravaged, dusty town that was just coming back to life after years of neglect. Remnants of the civil war could still be seen: in the walls of buildings that had been pockmarked by bullets and shrapnel, the carcasses of old abandoned tanks, and a local administration that was largely run by the former cadres of the TPLF, as a civilian administration had not yet been installed.

Although they were repatriating to Ethiopia from Sudan, the Tigrayans were not returning to their highland communities of origin. They were settled by the new regional administration into an area of northwest Ethiopia that had once been part of the Gondar province, but had been newly incorporated into the Tigray region in a process of redistricting that took place as soon as the Tigrayan-led government took power in 1991.

Repatriating 25,000 Tigrayans to these western lowlands became a way of laying claim to the land. Most were settled onto plots that had made up the unsuccessful state farms under the Marxist “Derg” government that had controlled the area from 1974-91 in the areas known as Mai Kadra, Rawayan and Adabai.

Life in the first years for newly repatriated refugees was difficult. They had to rebuild their lives from virtually nothing and learn to farm new crops using different methods than they had been accustomed to in their original homes. The Tigray region was faced with enormous post-war reconstruction needs, and many of the returnees in these three sites felt that they had been forgotten by the regional authorities once they returned. They received only meagre food and cash assistance for the first few months after returning and then were expected to become self sufficient. Gradually, however, people came to think of this place as home .

At first, people in the local area got along with each other reasonably well. Amhara, Tigrayan, Welkait and other ethnic groups coexisted peacefully. The strongest resentment to the redrawing of regional boundaries to incorporate the area into Tigray region seemed to come from further away – from the city of Gondar a day’s drive to the south and the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa in the centre of the country. In these places the symbolism of shifting regional boundaries and seizure of land fed into a growing narrative of resentment against the Tigrayan-dominated central government.

Explosion of violence

These tensions have escalated over the years. The Humera area was largely isolated by the Ethiopia-Eritrea border war which lasted for two decades from 1998 to 2018. The main route for transporting sesame, its largest cash crop, out of the area – through Eritrea – was closed, and the town’s location along the banks of the Tekezze River which separates the two countries in the west was within the militarised zone.

Since coming to power in 2018, Abiy Ahmed, the first Oromo prime minister, has made overtures to the Eritrean president, Isaias Afewerki, seeking to end the border conflict with that country and implement the peace treaty originally agreed in 2000. His efforts helped him secure the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize .

But internally he has been focusing his efforts on weakening the Tigrayan-led government. He has replaced the former ruling party with a new Prosperity Party, which the former Tigrayan leadership has refused to join. When national elections were postponed, citing the risks posed by COVID-19, the Tigrayan regional government went ahead and held their own election on September 9. The central government refused to recognise the results and declared its intention to install an administration of its own choosing, thereby ramping up the tensions between the centre and the region.

The real losers in this political crisis are, of course, the civilians caught in the middle of the fighting. For the people of Humera and its surroundings, who fled civil war during the 1980s, then lived through the border war with Eritrea and are now again on the front lines, the fighting brings back the trauma of past wars and displacements.

The grievances of each side are real and legitimate. But the violence that is now spreading across Tigray and into Eritrea and neighbouring regions is not resolving them. It is only adding to them, heaping pain and outrage onto a dangerous bonfire that is already burning out of control.