Image credit: Nicolas Datiche/Getty Images

Image credit: Nicolas Datiche/Getty Images

CONCRETE: THE MATERIAL THAT'S 'TOO VAST TO IMAGINE'

RICHARD FISHER & JAVIER HIRSCHFELD

There is so much concrete in the world that soon it will outweigh all living matter – including us. In the latest in our Anthropo-scene series, we explore the material's global reach, occasional beauty, and unimaginable scale.

Ages of human history have often been named after the materials that our ancestors mastered at that time: stone, bronze or iron.

If future archaeologists do the same for us, what material might they choose to define the 21st Century? Silicon? Plastic? Both are candidates, shaping the world for better and for worse. But if the decision were based on scale alone, then there can be only one answer: we are living in the age of concrete.

There are few human-made substances on Earth that are quite so ubiquitous. Concrete is what the philosopher-ecologist Timothy Morton calls a " hyperobject " – something so enormous and widespread that it cannot be fully contemplated with the mental faculties that we have. If you attempt to picture the entirety of the world's concrete in the mind's eye, you soon realise that it's impossible.

However, Emily Elhacham of the Weizmann Institute of Science and colleagues recently attempted to give it a shot. Their goal was to better understand humanity's impact during the Anthropocene by totting up the weight of all inanimate human-made objects on Earth . As part of their calculations, they found that concrete accounts for around half of all human-made things – the single biggest category of anthropogenic material. And if its rate of growth continues, it will overtake the total weight of Earth's biomass sometime around 2040.

Try to picture that in the mind's eye: there is a day approaching soon when there will be a greater weight of concrete on Earth than every single tree in every forest, every fish in every sea, every farm animal in every field, and every person breathing, walking, living right now.

- Why the world is running out of sand

- The world's growing concrete coasts

- How Shanghai will fossilise

How to make sense of this scale? When we encounter an outcrop of granite or limestone, poking out at the surface, its presence can hint at a far deeper and vaster bedrock beneath. We can take the same approach with a single concrete building, wall or slab – each individual instance can be approached as merely the local emergence of a material with an unseen and unimaginable geological reach.

So, in this edition of BBC Future's photographic series Anthropo-scene , we decided to tour a selection of what you might call concrete "outcrops". Each visual example from around the world can help us to understand the material – and our relationship with it – a little more clearly.

Think of concrete, and modernist architecture often comes to mind, such as the imposing buildings of Le Corbusier in France (Credit: Alamy)

Le Corbusier also designed The Palace of Assembly, a government building in Chandigarh, India (Credit: Alamy)

The Tricorn Centre in Portsmouth, UK, which was built in 1966, as concrete use was beginning to explode (Credit: Getty Images)

From the air, it looks like the bend of a river, but it is a concrete canal near the coast of Chile to mitigate tsunamis (Credit: Guillermo Salgado/Getty Images)

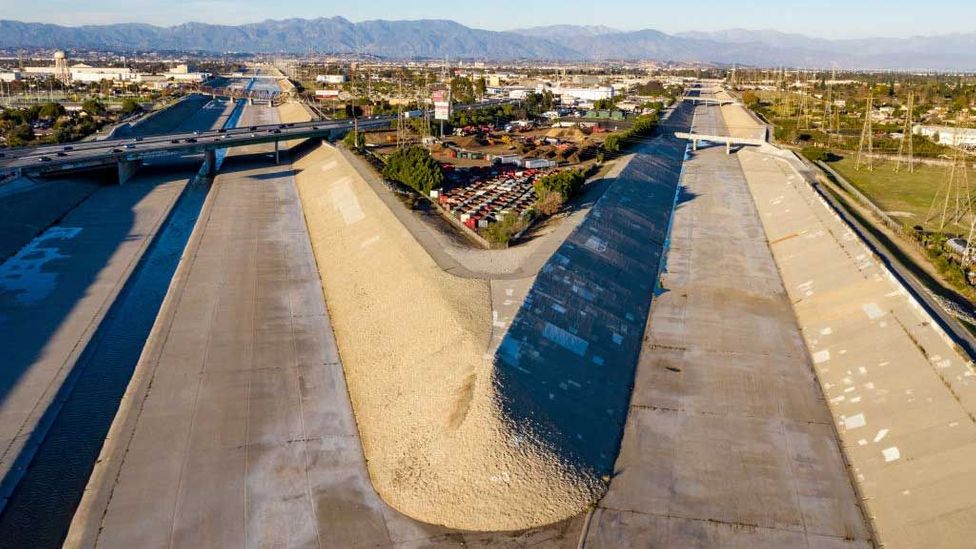

The Los Angeles River was once free-flowing, but after flooding in the early 20th Century, it was encased in a more controllable channel (Credit: Brian van der Brug/Getty Images)

Children play on a concrete plain created to protect a mosque in Hasankeyf, Turkey from the deliberate flooding of a reservoir (Credit: Bulent Kilic/Getty Images)

Concrete builds, but it can also divide. A controversial barrier in the town of Beit Jala in the West Bank (Credit: Thomas Coex/Getty Images)

A massive protective seawall in Japan hides the ocean from view… (Credit: Nicolas Datiche/Getty Images)

…apart from a rare glimpse. The wall is designed to protect Japan's coast from future tsunamis (Credit: Carl Court/Getty Images)

Nature, subsumed: towering walls of concrete entomb forests on mountainsides in south-west China, to build a major dam (Credit: Johannes Eisele/Getty Images)

The interior concrete lining of the Mont d'Ambin Base Tunnel, part of a high-speed rail link connecting Lyon, France with Turin, Italy (Credit: Emanuele Cremaschi/Getty Images)

A child walks inside sewage concrete rings at Jamtola refugee camp in Ukhia, Bangladesh (Credit: Munir Uz Zaman/Getty Images)

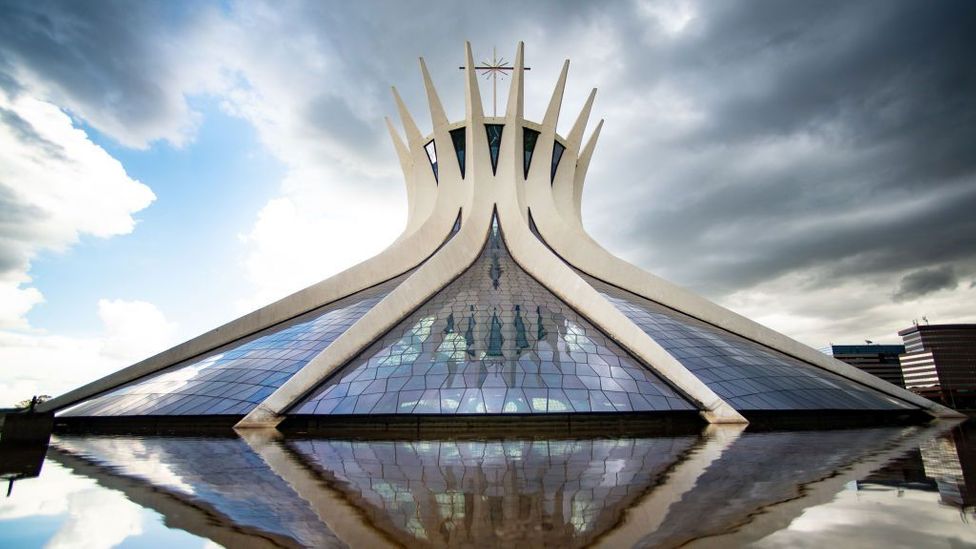

Concrete can also be stunning, however, such as the Brasilia Cathedral in Brazil (Credit: Andressa Anholete/Getty Images)

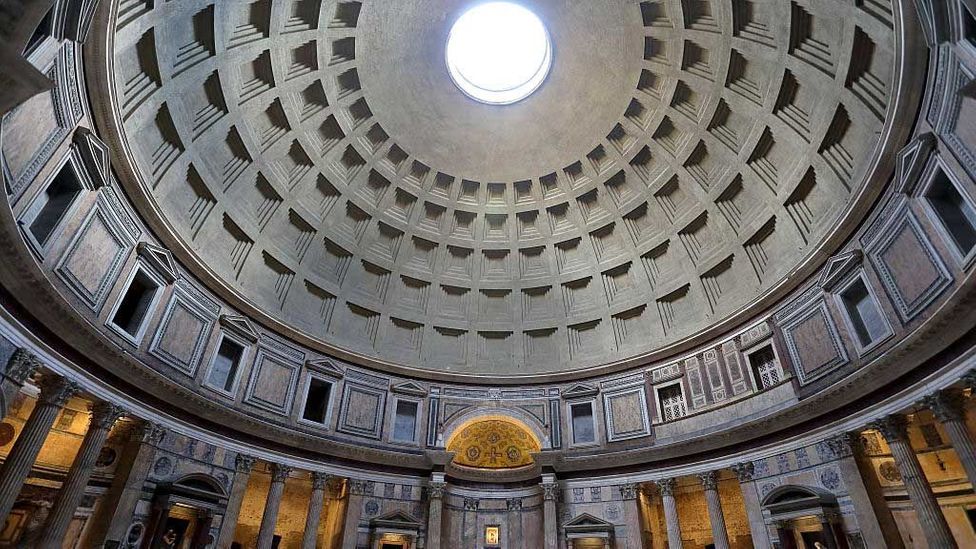

The Pantheon in Rome, Italy – the world's largest unreinforced concrete dome was built in the 2nd Century AD (Credit: Athanasios Gioumpasis/Getty Images)

For a German artwork, Time Pyramid, a concrete block will be placed every decade for 1,000 years. Eventually, a pyramid will form (Credit: JuSt-Wemding/Wikipedia/CC BY-SA.3.0)

A rare time where concrete works with nature: balls designed to foster reef growth offshore at Puerto Quetzal, in Guatemala (Credit: Orlando Estrada/Getty Images)

The reef-balls are dropped into the sea, where organisms will hopefully colonise them (Credit: Orlando Estrada/Getty Images)

Concrete "tetrapods" protect a tidal island from the ocean in Kesennuma, Japan (Credit: Carl Court/Getty Images)

Up close, concrete mixed with aggregate can look almost geological – only its shape reveals its human origins (Credit: Getty Images)

It may be strong, but all things erode eventually. Chunks of concrete and asphalt hang over a cliff in Pacifica, California after a storm (Credit: Josh Edelson/Getty Images)

Eroded concrete causes flooding from the Oroville Dam spillway in California (Credit: Kelly M. Grow/Getty Images)

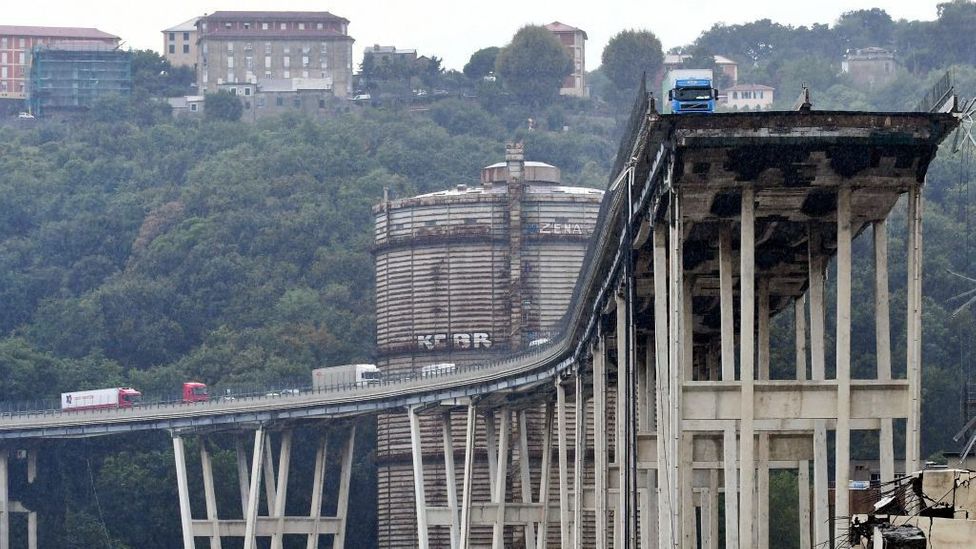

The slender concrete legs of a bridge in Italy that collapsed in 2018 (Credit: Valery Hache/Getty Images)

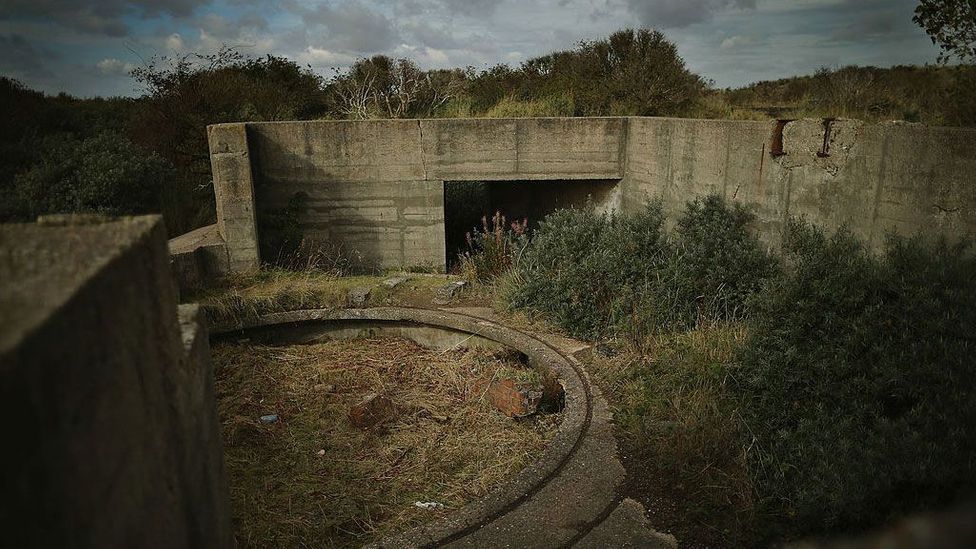

Eventually, nature takes back everything: a concrete military bunker is reclaimed by dunes at Spurn Point in Yorkshire, UK (Credit: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images)

The ocean laps against the temporary Mulberry harbour, placed on the French coast during WWII to allow rapid offloading of cargo (Credit: Damien Meyer/Getty Images)

An old quarry building on the UK's Titterstone Clee Hill, which also has Bronze and Iron Age forts. What will future archaeologists make of it? (Credit: Mike Kemp/Getty Images)