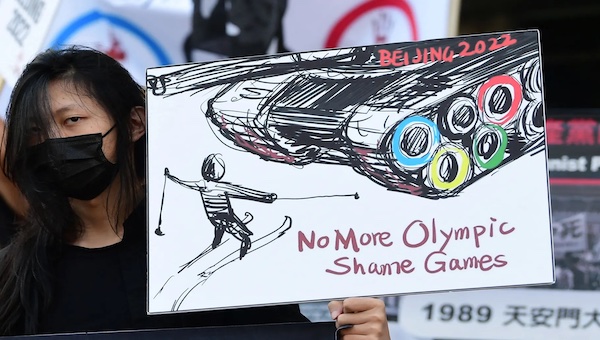

Frederic J. Brown/AFP via Getty Images

Frederic J. Brown/AFP via Getty Images

WHAT THE US’S DIPLOMATIC BOYCOTT OF THE 2022 BEIJING OLYMPICS DOES — AND DOESN’T — MEAN

BY: JEN KIRBYSITE: VOX

TRENDING

Activism

Belief

Big Pharma

Conspiracy

Cult

Culture

Economy

Education

Entertainment

Environment

Global

Government

Health

Hi Tech

Politics

Prophecy

Science

Social Climate

Universe

War

It’s more “symbolic than substantial,” but that doesn’t mean it’s consequence-free.

The opening ceremonies for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics are less than two months away, and some potential guests have already said they’re not showing up. We’re talking about US officials.

President Joe Biden’s administration said this week that it would not send US government officials to the Beijing Games in protest of China’s human rights violations, including its abuses against the Uyghurs in Xinjiang and anti-democratic crackdown in Hong Kong. The United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada also said this week that they will keep their delegations home.

This diplomatic boycott isn’t a full-on protest of the games, and won’t prevent athletes from participating in the 2022 Olympics. It won’t affect the spectacle of the event all that much, although lots of skiers will probably be asked about it. And despite some pressure from activists and human rights advocates, corporate sponsors — a.k.a. the money behind it all — have been largely silent.

All of this makes the US diplomatic boycott “more symbolic than substantial,” Zhiqun Zhu, a professor of political science and international relations at Bucknell University, wrote in an email.

That symbolism can still needle the Chinese government, especially now that countries beyond the US have joined, and even more so if others follow suit. The Olympics matter to Beijing — maybe not as much as its coming-out party in the 2008 Summer Games, but President Xi Jinping still wants to signal international prestige to the world and to his domestic audience, especially amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Chinese government has pushed back pretty hard against the boycotts. Before they became real, China warned of “resolute countermeasures,” without specifying what those might be. Since the boycott announcements, Chinese officials basically said that’s cool, but you actually weren’t even invited anyway.

“Those politicians who clamor to boycott for political self-interest are showing off and hyping things up, no one cares whether they come or not,” China’s foreign ministry said in a statement following reports of Australia’s possible boycott. “It has no influence on Beijing’s success in hosting the Olympics.”

Yet it’s pretty heated rhetoric, and this “diplomatic boycott” could serve to deepen tensions between the United States and China, and for something that won’t reverse China’s abuses in Xinjiang, Tibet, or Hong Kong. It also might make it even harder to work together on things Beijing and Washington do need to cooperate on, whether it’s climate change or North Korea or the Iran nuclear deal.

This relatively minor “diplomatic boycott” could still have geopolitical consequences, even if the message it sends to China ultimately won’t alter the government’s policies, or really change the course of the Olympic Games at all. As Dan Chen, assistant professor of political science at the University of Richmond, pointed out: “Once the competition starts, the people’s attention will probably be on how many gold medals and things like that.”

The limits to a “diplomatic boycott”

Olympic boycotts are tricky things. The last time the US tried it in earnest — with no diplomats, no athletes, no presence at all — was during the 1980 Moscow Olympics, to protest the Soviet Union’s Afghanistan invasion. Washington got some allies to go along, and Moscow registered America’s displeasure, but the effort did little to sway policy. It also kind of backfired: It very publicly denied some athletes their one shot at a medal, and it meant the Soviets absolutely cleaned up in the medal count, a nice propaganda win.

“The things that motivate nation-states are far more significant than how many gold medals you win,” Nicholas Sarantakes, an associate professor of strategy and policy at the US Naval War College and author of Dropping the Torch: Jimmy Carter, the Olympic Boycott, and the Cold War, told me earlier this year. “It’s been tried several times. And it fails every time.”

What the US is doing isn’t a full-on boycott, of course; it’s basically just keeping a Cabinet secretary or two and some other officials stateside in February. This avoids the messiness of pressuring the US Olympic & Paralympic Committee (which is an independent body) and its athletes, while at the same time taking a public stand against China’s egregious human rights abuses. It doesn’t go as far as some advocates wanted, which was a relocation or full boycott of what they call the “genocide Olympics.”

It also doesn’t go as far as some lawmakers wanted. Republican Sen. Tom Cotton called the diplomatic boycott “a half-measure,” and wanted to pull athletes, too. His colleague Sen. Marco Rubio has called on sponsors to pull advertising and acknowledge the genocide in Xinjiang, and to pressure the International Olympic Committee to move the games out of Beijing, even if that means postponing them — something that, if it hasn’t happened already, is not going to happen now.

Experts said some of this domestic pressure at home may have forced Biden to act, and the administration has split the difference between full-on boycott and nothing at all. “A diplomatic boycott is maybe politically necessary for the Biden administration, given the bad state of the relationship, and also the very anti-China atmosphere in Washington,” said Mary Gallagher, a professor of political science and director of the Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Michigan.

Biden’s move was also bolstered by US allies, like Australia and Canada (which have their own disputes with China), joining in. But France, for example, has said it will not do the diplomatic boycott. Still, the bigger the cohort protesting, the more China is to likely take notice — and it will show, to some degree, that the US can still get allies and partners to come along with it.

China, again, is not going to change its policies in response to external pressure, especially not around the Olympics. And even though Beijing is brushing this off very publicly, the boycott could still disappoint them, experts said, and it will likely reinforce the notion that there’s no room for real cooperation with the United States, especially since the announcement comes as the US is hosting its Summit for Democracy, which is really a counter-China conference.

At the same time, as experts told me, China is not blindsided by this reaction. In 2008, human rights criticism around the Olympics caught the Chinese Communist Party off-guard. Now they’re prepared, and know how to respond: by spinning it for the domestic audience and pushing back against critics abroad. “The bigger point that [Chinese officials] make in responding to the boycott is that they perceive this as another American effort to try to contain China, especially when China has become more powerful, wealthier — and America’s using human rights, hypocritically, to try to contain China,” Chen said.

In lots of ways, the back-and-forth around the boycott shows the challenges of responding meaningfully to China’s human rights abuses. The United States and other governments have credibly called the Chinese Communist Party’s internment and forced labor of Uyghurs a genocide, and have sanctioned Chinese government officials for actions in Xinjiang and Hong Kong. The US has passed legislation to protect democracy in Hong Kong, and the House recently passed a bill to limit imports from Xinjiang tied to forced labor. China, so far, has largely resisted the pressure.

The boycott barely adds to the pressure, but it also comes with the sense that countries can’t just do the Olympics as usual. “It’s striking, of course, with 1980 in comparison,” Gallagher said. “Because both the Trump and the Biden administration use the ‘g-word’ ... to label the what the Chinese government is doing in Xinjiang. But at the same time, even genocide doesn’t earn a full boycott.”

Some advocates say that just talking about any kind of boycott in connection to the Olympic Games may raise visibility of China’s atrocities — a small victory, but a victory nonetheless. It may also put pressure on sports bodies, in this case, the International Olympic Committee, to rethink these decisions in the future. (The IOC has said it “respects” the diplomatic boycotts.) This feels especially poignant in the wake of the disappearance of tennis star Peng Shuai and the Women’s Tennis Association’s decision to pull out of China; it may not alter China’s authoritarian policies, but it is stating, at least, that they are unacceptable.

Click 3 Dots Below to View Complete Sidebar